Tajikistan - TJ - TJK - TJK - Central Asia

Tajikistan Images

Tajikistan Factbook Data

Diplomatic representation from the US

embassy: 109-A Ismoili Somoni Avenue (Zarafshon district), Dushanbe 734019

mailing address: 7090 Dushanbe Place, Washington DC 20521-7090

telephone: [992] (37) 229-20-00

FAX: [992] (37) 229-20-50

email address and website:

DushanbeConsular@state.gov

https://tj.usembassy.gov/

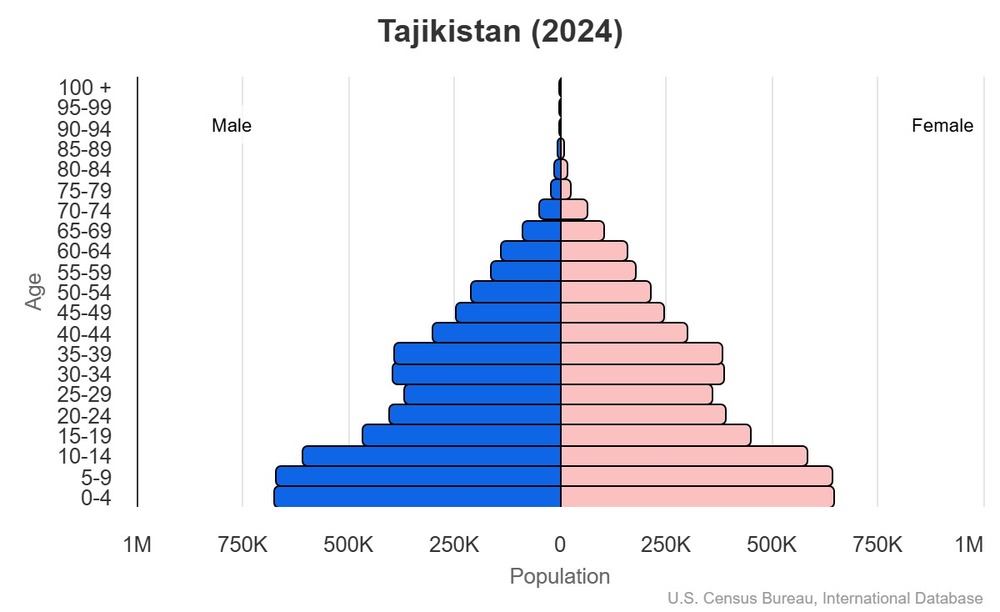

Age structure

15-64 years: 59.3% (male 3,086,964/female 3,071,642)

65 years and over: 3.9% (2024 est.) (male 181,382/female 223,411)

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

Geographic coordinates

Sex ratio

0-14 years: 1.04 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 1 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.81 male(s)/female

total population: 1.01 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

Natural hazards

Area - comparative

Military service age and obligation

note: in August 2021, the Tajik Government removed an exemption for university graduates but began allowing men to pay a fee in order to avoid conscription, although there is a cap on the number of individuals who can take advantage of this exemption

Background

The Tajik people came under Russian imperial rule in the 1860s and 1870s, but Russia's hold on Central Asia weakened following the Revolution of 1917. At that time, bands of indigenous guerrillas (known as "basmachi") fiercely contested Bolshevik control of the area, which was not fully reestablished until 1925. Tajikistan was first established as an autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in 1924, but in 1929 the Soviet Union made Tajikistan as a separate republic and transferred to it much of present-day Sughd Province. Ethnic Uzbeks form a substantial minority in Tajikistan, and ethnic Tajiks an even larger minority in Uzbekistan. Tajikistan became independent in 1991 after the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the country experienced a civil war among political, regional, and religious factions from 1992 to 1997.

Despite Tajikistan's general elections for both the presidency (once every seven years) and legislature (once every five years), observers note an electoral system rife with irregularities and abuse, and results that are neither free nor fair. President Emomali RAHMON, who came to power in 1992 during the civil war and was first elected president in 1994, used an attack planned by a disaffected deputy defense minister in 2015 to ban the last major opposition party in Tajikistan. RAHMON further strengthened his position by having himself declared "Founder of Peace and National Unity, Leader of the Nation," with limitless terms and lifelong immunity through constitutional amendments ratified in a referendum. The referendum also lowered the minimum age required to run for president from 35 to 30, which made RAHMON's first-born son Rustam EMOMALI, the mayor of the capital city of Dushanbe, eligible to run for president in 2020. RAHMON orchestrated EMOMALI's selection in 2020 as chairman of the Majlisi Milli (the upper chamber of Tajikistan's parliament), positioning EMOMALI as next in line of succession for the presidency. RAHMON opted to run in the presidential election later that year and received 91% of the vote.

The country remains the poorest of the former Soviet republics. Tajikistan became a member of the WTO in 2013, but its economy continues to face major challenges, including dependence on remittances from Tajikistani migrant laborers in Russia and Kazakhstan, pervasive corruption, the opiate trade, and destabilizing violence emanating from neighboring Afghanistan. Tajikistan has endured several domestic security incidents since 2010, including armed conflict between government forces and local strongmen in the Rasht Valley and between government forces and informal leaders in Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast. Tajikistan suffered its first ISIS-claimed attack in 2018, when assailants attacked a group of Western bicyclists, killing four. Friction between forces on the border between Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic flared up in 2021, culminating in fatal clashes between border forces in 2021 and 2022.

Environmental issues

International environmental agreements

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

Military expenditures

2% of GDP (2023 est.)

1.9% of GDP (2022 est.)

1.2% of GDP (2021 est.)

1.1% of GDP (2020 est.)

Population below poverty line

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

Household income or consumption by percentage share

highest 10%: 26.4% (2015 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

Exports - commodities

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

Exports - partners

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

Administrative divisions

note: the administrative center name follows in parentheses

Agricultural products

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

Military and security forces

Tajik National Guard (TNG); Ministry of Internal Affairs: Internal Troops of Tajikistan; State Committee on National Security: Border Troops (aka Border Service) (2025)

note 1: the Mobile Forces are the airborne, air assault, mountain, and rapid reaction troops of the Armed Forces

note 2: the Tajik National Guard, formerly the Presidential Guard, is a paramilitary force under direct authority of the President; it is tasked with ensuring public safety and security, similar to the tasks of the Internal Troops; it also has ceremonial duties

Budget

expenditures: $3.036 billion (2023 est.)

note: central government revenues (excluding grants) and expenditures converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

Capital

geographic coordinates: 38 33 N, 68 46 E

time difference: UTC+5 (10 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the name means Monday in Persian; today's city was originally at the crossroads where a large bazaar was held on Mondays, or the second day (du) after Saturday (shambe)

Imports - commodities

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

Climate

Coastline

Constitution

amendment process: proposed by the president of the republic or by at least one third of the total membership of both houses of the Supreme Assembly; adoption of any amendment requires a referendum, which includes approval of the president or approval by at least two-thirds majority of the Assembly of Representatives; passage in a referendum requires participation of an absolute majority of eligible voters and an absolute majority of votes; constitutional articles, including Tajikistan’s form of government, its territory, and its democratic nature, cannot be amended

Exchange rates

Exchange rates:

10.799 (2024 est.)

10.845 (2023 est.)

11.031 (2022 est.)

11.309 (2021 est.)

10.322 (2020 est.)

Executive branch

head of government: Prime Minister Qohir RASULZODA (since 23 November 2013)

cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by the president, approved by the Supreme Assembly

election/appointment process: president directly elected by simple-majority popular vote for a 7-year term (two-term limit), but as the "Leader of the Nation," president has no term limit; prime minister appointed by the president

most recent election date: 11 October 2020

election results:

2020: Emomali RAHMON reelected president; percent of vote - Emomali RAHMON (PDPT) 92.1%, Rustam LATIFZODA (APT) 3.1%, other 4.8%

2013: Emomali RAHMON reelected president; percent of vote - Emomali RAHMON (PDPT) 84%, Ismoil TALBAKOV CPT) 5%, other 11%

expected date of next election: 2027

Flag

meaning: red stands for the sun, victory, and the unity of the nation; white for purity, cotton, and mountain snows; green for Islam and nature's bounty; the crown symbolizes the Tajik people; the stars represent the number seven, which is considered a symbol of perfection and the embodiment of happiness

Independence

Industries

Judicial branch

judge selection and term of office: Supreme Court, Constitutional Court, and High Economic Court judges nominated by the president and approved by the National Assembly; judges of all 3 courts appointed for 10-year renewable terms with no term limits, but the last appointment must occur before the age of 65

subordinate courts: regional and district courts; Dushanbe City Court; viloyat (province-level) courts; Court of Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region

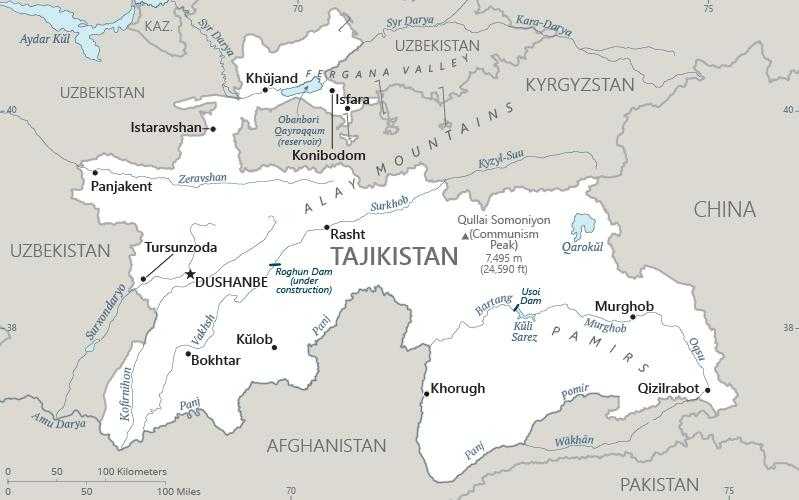

Land boundaries

border countries (4): Afghanistan 1,357 km; China 477 km; Kyrgyzstan 984 km; Uzbekistan 1,312 km

Land use

arable land: 6.1% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 1.5% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 20.4% (2023 est.)

forest: 3.1% (2023 est.)

other: 69% (2023 est.)

Legal system

Legislative branch

legislative structure: bicameral

Literacy

Maritime claims

International organization participation

National holiday

Nationality

adjective: Tajikistani

Natural resources

Geography - note

Political parties

Democratic Party or DPT

Party of Economic Reforms or PERT

People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan or PDPT

Socialist Party of Tajikistan or SPT

Railways

broad gauge: 680 km (2014) 1.520-m gauge

Suffrage

Terrain

Government type

Country name

conventional short form: Tajikistan

local long form: Jumhurii Tojikiston

local short form: Tojikiston

former: Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic

etymology: the Persian suffix -ostan means "land," so the country name means "Land of the Tajik [people];" the name Tajik comes from the Sanskrit tajika, a name originally used to distinguish Arabs from Turks and derived from the Tay, an Arab people

Location

Map references

Irrigated land

Internet users

Internet country code

Refugees and internally displaced persons

IDPs: 238 (2024 est.)

stateless persons: 4,466 (2024 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate)

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

Total renewable water resources

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

male: 12 years (2024 est.)

female: 11 years (2024 est.)

Urbanization

rate of urbanization: 2.73% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

Broadcast media

Drinking water source

urban: 95.6% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 76.6% of population (2022 est.)

total: 81.9% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 4.4% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 23.4% of population (2022 est.)

total: 18.1% of population (2022 est.)

National anthem(s)

lyrics/music: Gulnazar KELDI/Sulaimon YUDAKOV

history: adopted 1994; after the fall of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan kept the music of its Soviet-era anthem, but adopted new lyrics

Major urban areas - population

International law organization participation

Physician density

Hospital bed density

National symbol(s)

Mother's mean age at first birth

GDP - composition, by end use

government consumption: 10.7% (2023 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 28.3% (2023 est.)

investment in inventories: 3.4% (2023 est.)

exports of goods and services: 17.2% (2023 est.)

imports of goods and services: -48.4% (2023 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

Dependency ratios

youth dependency ratio: 62.2 (2024 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 6.6 (2024 est.)

potential support ratio: 15.2 (2024 est.)

Citizenship

citizenship by descent only: at least one parent must be a citizen of Tajikistan

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: 5 years or 3 years of continuous residence prior to application

Population distribution

Electricity access

electrification - urban areas: 99%

electrification - rural areas: 100%

Civil aircraft registration country code prefix

Sanitation facility access

urban: 98.9% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 99.6% of population (2022 est.)

total: 99.4% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 1.1% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 0.4% of population (2022 est.)

total: 0.6% of population (2022 est.)

Ethnic groups

Religions

Languages

major-language sample(s):

Китоби Фактҳои Ҷаҳонӣ, манбаи бебадали маълумоти асосӣ (Tajik)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

note: Russian widely used in government and business

Imports - partners

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

Elevation

lowest point: Syr Darya (Sirdaryo) 300 m

mean elevation: 3,186 m

Health expenditure

6.4% of national budget (2022 est.)

Military - note

Tajikistan is the only former Soviet republic that did not form its armed forces from old Soviet Army units following the collapse of the USSR in 1991; rather, Russia retained command of the Soviet units there while the Tajik government raised a military from scratch; the first ground forces were officially created in 1993 from groups that fought for the government during the Tajik Civil War (2025)

Military and security service personnel strengths

Terrorist group(s)

note 1: US-designated foreign terrorist groups such as the Islamic Jihad Union, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham-Khorasan Province have operated in the area where the Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Tajik borders converge and ill-defined and porous borders allow for the relatively free movement of people and illicit goods

note 2: details about the history, aims, leadership, organization, areas of operation, tactics, targets, weapons, size, and sources of support of the group(s) appear(s) in the Terrorism reference guide

Total water withdrawal

industrial: 1.61 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 7.378 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

Waste and recycling

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 13.9% (2022 est.)

Major watersheds (area sq km)

Major rivers (by length in km)

note: [s] after country name indicates river source; [m] after country name indicates river mouth

National heritage

selected World Heritage Site locales: Proto-urban Site of Sarazm (c); Tajik National Park (Mountains of the Pamirs) (n); Silk Roads: Zarafshan-Karakum Corridor (c); Tugay forests of the Tigrovaya Balka Nature Reserve (n); Cultural Heritage Sites of Ancient Khuttal (c)

Child marriage

women married by age 18: 8.7% (2017)

Coal

consumption: 2.297 million metric tons (2023 est.)

exports: 475,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 147,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

proven reserves: 4.075 billion metric tons (2023 est.)

Electricity generation sources

hydroelectricity: 92.6% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

Natural gas

consumption: 43.767 million cubic meters (2023 est.)

imports: 24.196 million cubic meters (2023 est.)

proven reserves: 5.663 billion cubic meters (2021 est.)

Petroleum

refined petroleum consumption: 31,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

crude oil estimated reserves: 12 million barrels (2021 est.)

Currently married women (ages 15-49)

Remittances

37.8% of GDP (2023 est.)

49.9% of GDP (2022 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

Legislative branch - lower chamber

number of seats: 63 (all directly elected)

electoral system: mixed system

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 3/2/2025

parties elected and seats per party: People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan (PDPT) (49); Agrarian Party of Tajikistan (APT) (7); Party of Economic Reforms of Tajikistan (PERT) (5); Other (2)

percentage of women in chamber: 28.6%

expected date of next election: March 2030

Legislative branch - upper chamber

number of seats: 33 (25 indirectly elected; 8 appointed)

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 3/28/2025

percentage of women in chamber: 30.3%

expected date of next election: March 2030

National color(s)

Particulate matter emissions

Labor force

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

Youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24)

male: 30% (2024 est.)

female: 23.3% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

Debt - external

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

Maternal mortality ratio

Reserves of foreign exchange and gold

$3.847 billion (2022 est.)

$2.499 billion (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

Unemployment rate

11.6% (2023 est.)

11.7% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

Population

male: 5,221,818

female: 5,172,245

Carbon dioxide emissions

from coal and metallurgical coke: 4.676 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 3.855 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from consumed natural gas: 86,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

Area

land: 141,510 sq km

water: 2,590 sq km

Taxes and other revenues

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

Real GDP (purchasing power parity)

$46.467 billion (2023 est.)

$42.905 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Airports

Gini Index coefficient - distribution of family income

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

Inflation rate (consumer prices)

3.9% (2018 est.)

7.3% (2017 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

Current account balance

$584.022 million (2023 est.)

$1.635 billion (2022 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

Real GDP per capita

$4,500 (2023 est.)

$4,200 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Broadband - fixed subscriptions

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2022 est.) less than 1

Obesity - adult prevalence rate

Energy consumption per capita

Electricity

consumption: 15.275 billion kWh (2023 est.)

exports: 3.101 billion kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 714.025 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 3.94 billion kWh (2023 est.)

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

Imports

$5.931 billion (2023 est.)

$5.261 billion (2022 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

Exports

$2.105 billion (2023 est.)

$1.753 billion (2022 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

Heliports

Telephones - fixed lines

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 5 (2022 est.)

Alcohol consumption per capita

beer: 0.38 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0.01 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 0.45 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

male: 70.1 years

female: 73.8 years

Real GDP growth rate

8.3% (2023 est.)

8% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

Industrial production growth rate

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

GDP - composition, by sector of origin

industry: 33.6% (2023 est.)

services: 34.7% (2023 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

Education expenditure

19.3% national budget (2024 est.)

Economic overview

lower-middle-income Central Asian economy; large infrastructure projects, including Rogun Dam, and a push towards green development and digitalization driving growth; strong metal mining, electricity, and manufacturing industries; challenges include land scarcity, climate vulnerability, and complex bureaucratic processes for investors

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions

Diplomatic representation in the US

chancery: 1005 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20037

telephone: [1] (202) 223-6090

FAX: [1] (202) 223-6091

email address and website:

tajemus@mfa.tj

https://mfa.tj/en/washington

Gross reproduction rate

Net migration rate

Median age

male: 22.3 years

female: 23.2 years

Total fertility rate

Infant mortality rate

male: 24.3 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 18.9 deaths/1,000 live births

Telephones - mobile cellular

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 119 (2021 est.)